I’ve been progressively building the argument that we educators need to help our students move beyond relativism, and towards an evaluativist level of understanding. But how can we achieve this?

A crucial first step is to engage students in dialogic argument with people who hold different points of view. We need to encourage students to take what’s been charmingly described as “friendly excursions into disequilibrium”.1

The value of this will be evident to anyone who has ever deliberated over a serious issue in the company of (sharp-witted) others. Having a sounding board helps us to formulate our ideas, and getting some pushback helps us to improve them. It follows that if we want to get our students thinking more deeply, reflectively and rigorously about an issue, we should get them engaged in thinking with others about it.

Thinking together affords opportunities that solitary introspection simply doesn’t: opportunities for students to frame problems better; to test out particular ideas and arguments; to overcome their respective cognitive biases; and to ‘jump out of the system’ of entrenched belief. It further promises an escape from the sort of recursive trap that Alan Watts alluded to when he quipped: “Trying to define yourself is like trying to bite your own teeth”.

Even more fundamentally, collaborative enquiry enables a community of students to establish and refine norms of effective thinking.

If students are flying solo, they’ll have a hard time assessing just how clear and precise –– not to mention how plausible and significant –– their ideas are. They might not even realise that clarity, precision, plausibility and significance are among the goals worth striving for. Such realisations dawn, Peter Ellerton suggests, in the very acts of arguing: in “explicitly evaluating arguments or justifying positions through constructing arguments.” He adds:

Thinking well is, in part, a result of our experiences of what others find persuasive and why, as well as reflection upon our own thinking to produce such persuasive effects. But thinking well is also about learning how to think with others, to in effect become part of a broader social cognition that can achieve more collectively than is possible individually.

Engaging in dialogic argument is what develops students’ respect for epistemic rigour and rational engagement –– values that each student will subsequently be in a position to internalise.

What we educators need to avoid is creating the conditions for a stalemate:

Instead, we want students to strengthen their respective arguments and come to a more nuanced understanding of the issues. For this, students need to directly engage with each other’s claims and reasons. And this in turn hinges on the sincere desire to pursue meaningful dialogue and follow the arguments where they lead.

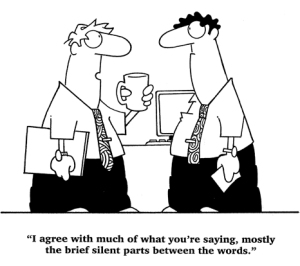

Unfortunately, class discussion usually falls short of this kind of engagement. Instead, we see a lot of what psychologist Deanna Kuhn calls ‘pseudo-argument’. On the surface, it resembles genuine dialogic argument in that students take turns to speak; they willingly express disagreement; they don’t hesitate to stake out a position on a controversial issue; and they even try to argue compellingly for the merits of their position. But they typically fail to engage with each other’s claims and reasons. They’re not working with each other’s ideas at all. For that matter, they might not even be paying attention to what others are saying. They’re merely interposing their own ideas.

Kuhn’s empirical studies lend substance to these claims. Each student participant seemed to believe that if they argued forcefully enough, their own position would prevail, ‘outshining any competitors, which [would] fade away without further consideration’. Comedian Tim Minchin has a striking metaphor to illustrate this belief. “Most of society’s arguments are kept alive by a failure to acknowledge nuance,” he says, continuing:

We tend to generate false dichotomies, then try to argue one point using two entirely different sets of assumptions, like two tennis players trying to win a match by hitting beautifully executed shots from either end of separate tennis courts.”

Erica Preston-Roedder highlights mutual dependence and responsiveness as guiding ideals of any ensemble. Within the context of a philosophical community, she writes:

responsiveness… means that my own ideas should be shaped by your contributions. If I develop my own ideas while talking to you, but do not actually do so in response to your offerings, then I have used you as a prop in a kind of monologue, not as a discussant.

So, what can teachers do about this? How can we banish pseudo-argument and achieve genuine dialogic argument in our classrooms? And how can we help students arrive at a shared appreciation for what makes for a worthy argument?

I’ll share some suggestions in my next post.

………………………………….

1 Quoting David and Roger Johnson of the Cooperative Learning Institute.

………………………………….

This is the fourth in a series of five posts about epistemological understanding, published in the lead-up to World Philosophy Day 2018. Return to the beginning of the series, or read on with the final post in the series, Beyond Parallel Play: Three keys to dialogic argument.

………………………………….

The Philosophy Club works with teachers and students to develop a culture of critical and creative thinking through collaborative enquiry and dialogue.

Thank you for writing such an interesting and thought-provoking post. I agree wholeheartedly that kids are not appropriately taught how to consume and reframe one another’s ideas to further challenge their own. Robust positions are crucial for self- identify and worldview frameworks. Unfortunately, I do think that there is too much credence given to students expressing their opinion in bubbles which do not really actively engage. It is important for students to be given a forum to speak their mind without fear of reprisal, but it shouldn’t be at the expense of intellectual debate. I hear people say the words ‘we are all entitled to an opinion’. Are we? Are we really entitled to an opinion if it may be weak or ineffectual, and if so, are we then entitled to spout it without challenge because it is inappropriate to engage in rigorous debate? I worry about future generations should they truly believe that the best way to relate to their fellow man is to exist on eggshells in matters of thought and idea sharing: both at the very foundation of human experience and accomplishment. As educators, it is crucial for us to think outside the box, so that we may encourage our students to do the same. You have given wonderful food for thought with your argument.

Thanks for your comment, Leesy, and congratulations on the launch of your blog! There are a few pieces in the media that I keep returning to in relation to the topic of this post. I’ve already quoted Peter Ellerton; he has a great TED talk entitled ‘Why you have the right to be heard but not to be taken seriously’, as well as some excellent pieces in The Conversation, like ‘Facts are not always more important than opinions: Here’s why’. I also remember Mike Gershon’s Guardian article ‘”It’s just my opinion” isn’t good enough’. I’ll paste the links below.

https://theconversation.com/facts-are-not-always-more-important-than-opinions-heres-why-76020

https://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/2012/jan/02/opinion-argument-free-speech