(Or, how to be inimitable)

We’re a motley crew, we Philosophy in Schools people. Our goals are so varied, it can be hard to say exactly what it is that unites us. The catchphrase ‘critical, creative and caring thinking’ is bandied around a lot, and there seems to be a general agreement that we should be promoting activities along these lines. But on close inspection, the catchphrase turns out to be something of a catch-all (and not a well-defined one, at that).

There isn’t yet a consensus about the meaning of ‘critical thinking’. It might refer to intellectual standards (like clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logic and fairness) that are helpful as we go about analysing and evaluating arguments in order to determine their validity and soundness. Alternatively, it might refer to dispositions, like active open-mindedness, scepticism, honesty and courage, which enable us to apply these intellectual standards properly.

Cartoon by Randy Glasbergen

‘Creative thinking’ tends to be even more ill-defined. I’ve previously tried to untangle its various meanings, and concluded that it might refer to using your imagination; or seeing things from new perspectives; or applying inventive and generative thinking. (And I’m sure this list is not exhaustive.)

Then we have ‘caring thinking’, which could be interpreted as caring for the wellbeing of others within a community of enquiry; or being concerned with interlocutors rightly understanding each other; or giving a damn about the truth.

And the ‘critical, creative and caring’ triumvirate is just the beginning of our dispersal of focus. In scatter-gun fashion, we declare sundry other intellectual goals, like promoting independent, self-correcting, reflective and metacognitive thinking – not to mention a slew of social and political goals, like promoting democratic citizenship; building self-propelling dialogic communities; and fostering personal responsibility and ethical awareness. The lists go on.

We set our sights on myriad aims, and we don’t always agree on what they should be. We’re a single tribe, but we are large, we contain multitudes.

When I started out in this field, I was drawn to the whole package. Collaborative philosophical enquiry seemed to gleam like a silver bullet, bursting with intellectual, human and civic potential.

Over the years, the sheen has dulled a bit.

This has something to do with the over-reach of claims about what the practice of collaborative philosophical enquiry can accomplish – claims that haven’t always been strongly borne out by evidence.

It has something to do with a misplaced desire for expediency; a desire to tick prescribed curricular boxes, such as boosting results in literacy and numeracy. (There do appear to be slight positive impacts in these areas, but they’re essentially side-effects.)

It has something to do with the inconsistent levels of expertise among practitioners, with some disappointingly sub-par facilitation being done in some places, to the detriment of participants and to the discredit of the movement as a whole.

And perhaps it also has something to do with the diffuse nature of the outcomes we’ve been seeking.

Some of the most widely vaunted benefits of collaborative philosophical enquiry relate to students’ socialisation, participation and wellbeing. There are reported improvements to students’ emotional self-regulation, social inclusion, respectful listening, self-esteem, confidence, empathy, student voice and so on. I don’t intend to trivialise these benefits, but I would suggest that they can be equally well accomplished by any other well-run ‘circle-time’ program.

So is it a case of collaborative philosophical enquiry being a ‘jack of all trades; master of none’?

Well, not exactly. It’s more like ‘jack of all trades; master of just a few’.

Where collaborative philosophical enquiry uniquely excels, I believe, is in cultivating students’ practical knowledge of:

- how to structure their thinking well;

- how to express their thinking clearly to others;

- how to work collaboratively to address controversies and problems;

- how to use evidence in an argument;

- how to question the assumptions underlying different points of view;

- how to evaluate different ideas, and discern which ideas are the most helpful or true; and

- how to reflect on the quality of their own reasoning, and how to improve it.

(This is an abbreviated list, adapted from a more extensive one set out on The Philosophy Foundation’s blog.)

Increasingly, I’ve been driven by a determination to build students’ (and teachers’) mastery in these particular areas. It’s a useful place to channel our energies, I think, because it’s here that the distinctive promise of collaborative philosophical enquiry lies. If we philosophy practitioners don’t focus in, then kids will almost certainly miss out.

………………………………….

Postscript #1, 6/10/2018

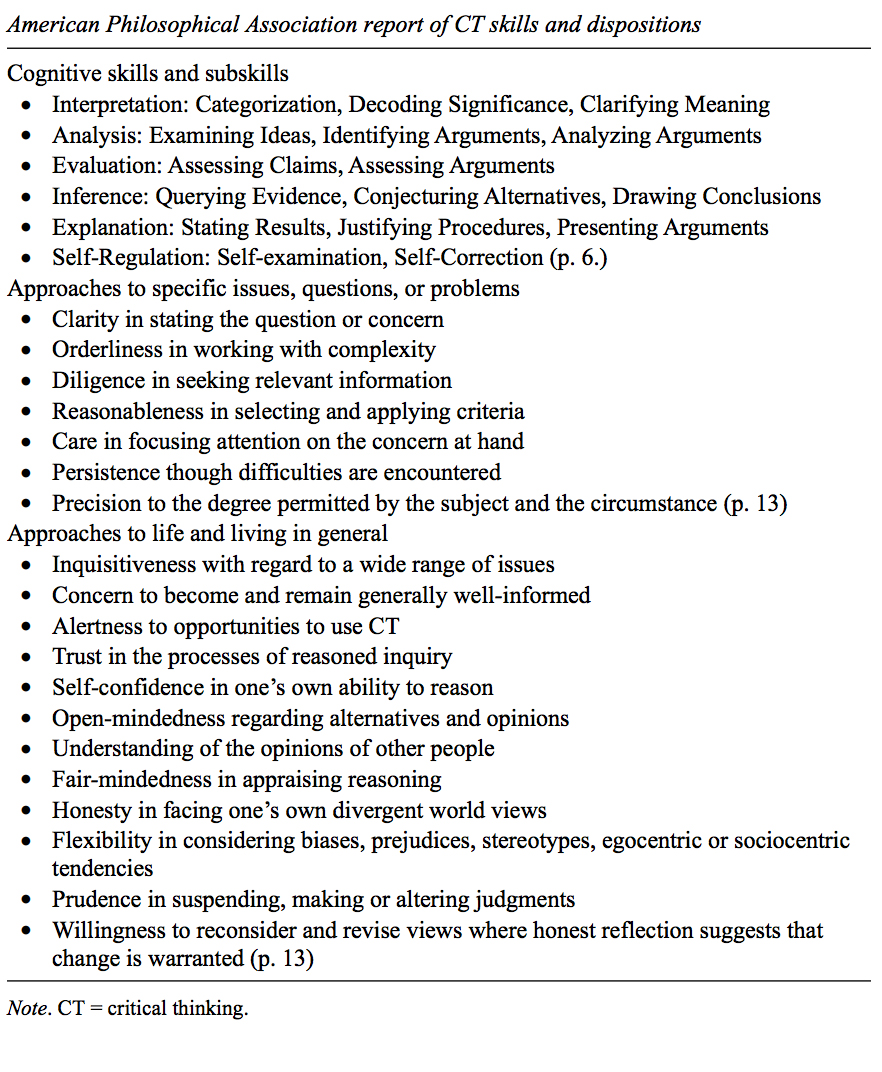

The table below reveals the breadth of critical thinking skills and dispositions as reported by the American Philosophical Association. It’s presented in the following form in the Appendix to Strategies for Teaching Students to Think Critically: A Meta-Analysis by Abrami et al, published in the Review of Educational Research, 2015.

………………………………….

Postscript #2, 12/12/2018

I’ve just come across the article Philosophy in Schools: Continuing the Conversation by Myfanwy Williams that was published last year on the philosophy news site Daily Nous. It’s pertinent to this post, so I’ll quote from it at length here:

Doing philosophy with children’ can mean many things, each of which may turn out to be more or less beneficial from different points of view. So when we ask, does the research tell us that teaching philosophy in schools makes children more numerate, literate, kinder, less aggressive, better verbal communicators, better listeners etc., we need to ask what ‘teaching philosophy’ means in different studies…What sort of benefits might we aim at or hope for? And what sorts of evidence would be appropriate?First, what are we looking for evidence of? That children grow into adults who are less intellectually stubborn? Or is it rapid gains in literacy and numeracy, as one might be led to think by the headlines last year? Is it making children better at critical thinking? Is it supporting non-cognitive development? Is it making children more able to and willing to question, and to pursue enquiry in the face of uncertainty? Is it shaping better future citizens? Is it about engaging with open-ended questions or learning the value of the examined life? Obviously there is room for different views; equally, doing philosophy with children might achieve some or even all of these things, at least if we do it well.Which leads us to the second point: it is bound to be hard – maybe impossible — to generate evidence for some of these aims… ‘empirical research’ won’t be enough to decide whether doing philosophy with children is worthwhile. Maybe studies can show certain benefits with one approach, at least in one cultural context; maybe another approach can be shown to have other benefits. Maybe some studies will show no measurable outcomes. But not every benefit will be worth the effort involved, and not everything that counts can be counted.

Postscript #3, 17/06/2021

Erica Preston-Roedder has something relevant to say here, too, in an article in Precollege Philosophy and Public Practice:

Since success in philosophical conversation takes many forms—some conversations are successful because they discover knock-down objections, others because they yield creative new ideas, yet others because they are simply enjoyable, etc.—mutual dependence only makes sense when the participants have a shared, or overlapping, vision for what constitutes a good philosophical discussion. Talk of ensemble and mutual dependence in philosophy, then, highlights the importance of communicating our vision of the purpose of a philosophical conversation.

………………………………….

The Philosophy Club works with teachers and students to develop a culture of critical and creative thinking through collaborative enquiry and dialogue.