“These hands are made for thinking!” a friend lamented yesterday as he struggled with a troublesome home-improvement project. I could relate. I’m as maladroit as the next philosopher (“we’re technically inept but conceptually brilliant,” a classmate of mine once quipped). So who’d have guessed that in recent months I would find myself spellbound by a podcast on forensic engineering?

But Brady Heywood is no ordinary engineering podcast. Without assuming any prior technical knowledge, the host Sean Brady1 offers profound insights into human and organisational causes of engineering failures, and reveals why – as he puts it – our decision making is not nearly as rational as we’d like to think.

Avoiding sensationalism at every turn, Brady analyses disastrous events, considering both technical and human factors, and investigates in each case whether simple human error is to blame, or whether we have actually designed whole systems that fail us. Collapsing bridges, buildings, and tunnels, aviation and spacecraft failures, and mining disasters are the refractive lenses that focus our attention on big issues – issues like corporate memory loss, complexity theory, and whether more information leads to better decision making.

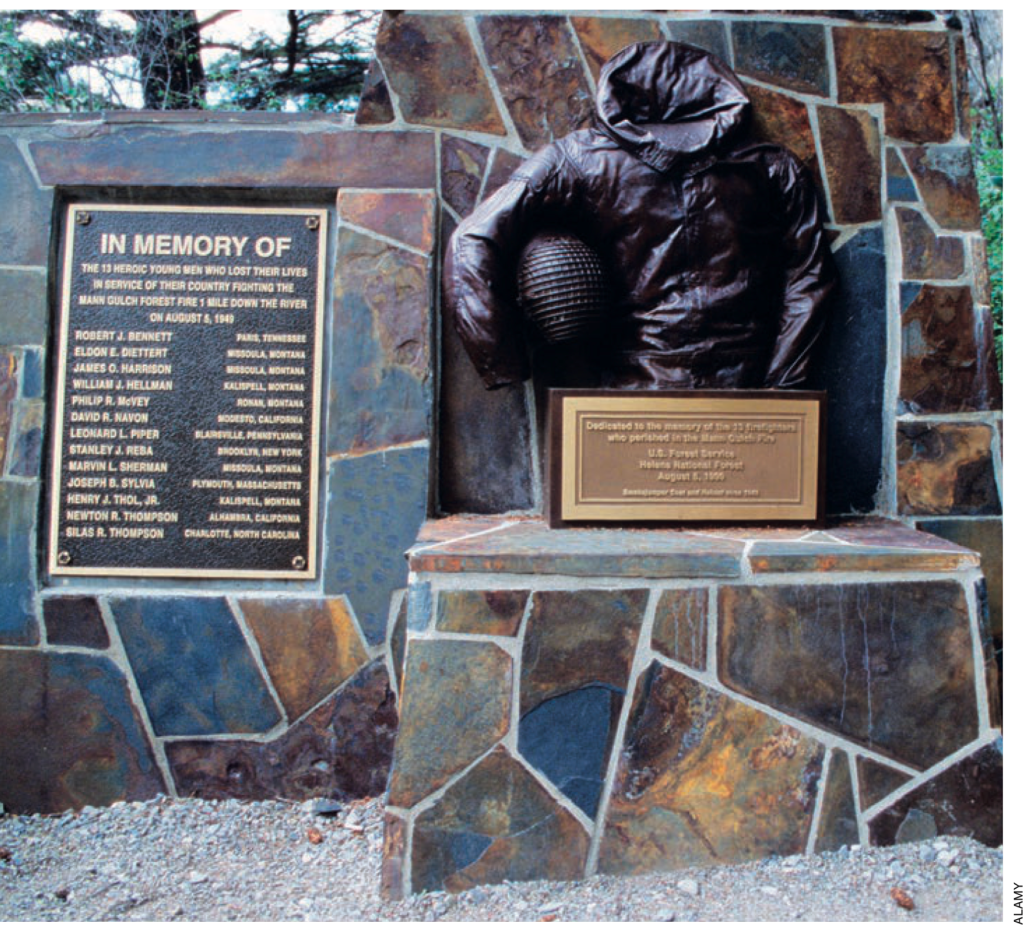

There’s one particularly compelling episode that I keep returning to: Why Expertise Can Hold Us Back. This episode explores the concept of ‘expertise bias’: how experts can become fixated on their established knowledge and tools, sometimes to the detriment of their decision-making. Brady tells the harrowing story of the 1949 Mann Gulch tragedy in which 13 of the US Forest Service’s smokejumpers (elite firefighters) lost their lives while battling a wildfire. It’s a devastating illustration the impact of expertise bias in a real-world, high-pressure situation. As Brady tells it2:

Suddenly, the fire spat hot embers into the grass at the foot of the northern slope… as the fire spread in the grass and moved towards them, now only 150 to 200 yards away, it became clear to [the foreman] Dodge that this was no ordinary fire: it … was a ‘blow-up’ – a tornado of fire… [The firefighters] were averaging about 1mph, an impressive speed given the terrain, but the fire was moving faster.

At this point, the foreman knew they were in real trouble. There was no more firefighting to be done. It was time to run for their lives. The men headed for the top of the ridge, according to standard firefighting practice.

With the fire 100 yards behind the men, Dodge gave the order to drop all tools – the shovels, the Pulaskis [axes] and the saws – so that the crew could run faster… Amazingly, many of the crew continued to hold onto their tools. It was as if they simply couldn’t drop them. One of the men… remembered pulling a shovel from [another’s] hand, but even he couldn’t drop it, instead looking for a lone tree to lean it against. He remembers the ranger… with his heavy pack still on, making no effort to remove it…. [seeming not] to consider that removing the pack would make him faster…

[Dodge] realised that the crew wouldn’t make it… The air was black with smoke, Dodge’s lungs were burning… It was then Dodge did something remarkable, believed to be the first use of a technique that has since become standard practice for wildfire fighters. He lit an escape fire. Taking a match, he lit the grass in front of him and watched flames race up the slope, burning swiftly through the grass. As the crew caught up with him, he shouted at them to get into the ashes before him… [The other firefighters] had no idea what he meant and thought he was mad to light another fire. They ignored him and … just ran past, fixated on getting to the ridge. With a wall of flame bearing down on him, Dodge wet his handkerchief and tied it round his face. He stepped into the ashes and lay face down… In a period of just 60 seconds, the fire would go on to swallow [eleven of the other men]…

For five long minutes the fire front passed over Dodge. He was lifted from the ground two or three times by its updraft… When [the fire] moved beyond him he stood up, red eyed from smoke and covered in soot… He looked up and down the slope. It was a barren wasteland…

Dodge had survived by lying down in an escape fire but, despite his orders, his men had ignored him and continued to clamber up the steep side of the gulch – many still clutching heavy tools – attempting to get to a ridge that was out of reach…Why did so many of these men cling to their heavy tools as the flames bore down? And why did they ignore Dodge’s escape fire and continue running, even though it should have been obvious to them that they would never make safe ground?

Brady suggests that what happened in Mann Gulch was much more than a fire: it was a lesson in how people make decisions under pressure. He goes on to describe a number of psychological experiments that demonstrate the cognitive concepts of priming (where background knowledge influences a person’s behaviour) and fixation (where a person gets stuck on a particular solution path, even if it’s not a useful one). It turns out that experts with deep domain knowledge are just as susceptible to priming and fixation as anyone else.“It is simply not possible to ‘switch off’ your knowledge and expertise”, Brady observes. “Its use is automatic and it appears to occur subconsciously.” As those psychology experiments reveal – and as the Mann Gulch tragedy illustrates – even if someone explicitly warns you about the risk of your expert knowledge clouding your judgement, you will likely deploy it anyway, especially if you’re in a stressful situation. And yet, there are certain situations in which dropping your tools is just what’s needed.

This is precisely what Dodge did when he broke through the tree line and realised the top of the ridge was out of reach. He had already dropped his physical tools, now he would drop his mental tool – his fixation on reaching the ridge. Running for a ridge is one of the tools used by the US Forest Service to escape harm… Usually, this is a good tool, but Dodge figured out in this particular circumstance that the tool was useless. So he dropped it. He was then left with his basic principles: fire required heat, oxygen and fuel. So he decided to deprive it of fuel. He lit an escape fire, the first time it had ever been attempted, inventing a new tool in the process… He showed extraordinary agility in his thinking about the issue… The rest of the crew’s response to Dodge’s escape fire shows just how hard our tools are to drop. Not only had they not dropped their tools – while some had dropped their physical tools, none appear to have dropped their mental fixation on reaching the ridge – they were unable to accept Dodge’s new tool, the escape fire. It was unfamiliar and didn’t fit into their existing expertise and training. So they ignored it…

For most of us, as with the crew, a new tool needs to be introduced not at a time of stress… but before. The importance of examining, evaluating and knowing if and when to drop your tools prior to a stressful period is illustrated in fire service training today. Firefighters are trained to run both with and without their tools, to demonstrate that they can run faster without tools. While this sounds obvious, the training actually embeds this tool in their expertise, and at times of stress they are now equipped to decide whether running or holding onto their tools is better.

Brady was speaking to an audience of engineers, but because I want to think about the significance of these remarks to my own practice and that of my colleagues, in the following passage I’ve cheekily replaced each of Brady’s references to ‘engineers’ with references to ‘philosophical inquiry practitioners’:

We carry tools and rely upon them, and Mann Gulch teaches us that when we come under pressure we will rely on these tools even when we should not. So, are there times we should drop our tools? And if we do, what are we left with? Well, that depends on the tools we actually carry, as individual [philosophical inquiry practitioners]. Are our tools… first principles [of philosophical inquiry]? Or are they the systems and processes we use to deliver [philosophical inquiry] as a service? If it is the latter, we should give our tools some serious thought. Yet many of us don’t, we simply get on with the business of applying them. And we carry an increasing number of ‘non-first principle’ tools… Are these tools aiding us to become better [practitioners] or are they replacing us, at least in a cognitive sense…? Many were intended to act as aids, but in the ever more commoditised world of delivering… services, the focus on the use of such tools is becoming greater and greater, to the detriment of fundamental principles. Mann Gulch teaches us that when [experts] find themselves in unusual situations and under pressure, they will apply these tools regardless of applicability. Indeed, if we become dependent on their use, we may find ourselves in situations where these tools have exceeded their limits without us knowing it.… [T]here will always be situations when over-reliance on these tools will let us down; when we get to that point, we will need to know their limitations and recognise when to drop them.

Having switched out the occupational references in this passage, I’m wondering to what extent the argument still holds, given that those of us who practise philosophical inquiry with school students or the general public typically pride ourselves on the reflectiveness and flexibility of our thinking. I think our trained self-awareness enables us – perhaps unlike other philosophers or educators – to sidestep certain kinds of expertise bias. For instance, unlike many philosophers, we’re conscious of avoiding the traps of using jargon, dismissing lay perspectives, or overvaluing abstract theories. Avoiding these biases has indeed become part of our training. And unlike many educators, we’re unlikely to find ourselves inadvertently valuing memorisation over critical thinking, assuming prior knowledge, or excluding student voices.

I suspect that there is nonetheless some truth to the claim that we’re in danger of making systemic and predicable errors due to our over-reliance on certain heuristics. I imagine that, like experts in any other field, we do remain prone to expertise bias. We might be inclined to dismiss alternative teaching methods, or fail to adapt to diverse learning styles. We might favour arguments that align with our own philosophical commitments, overlook unconventional ideas, or neglect interdisciplinary insights. We might get the balance wrong between rigour and accessibility. I’m interested to hear from my colleagues how our expertise bias might manifest itself, so we can help each other to practise steering clear.

Brady closes by quoting the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu: “In pursuit of knowledge, every day something is acquired; in pursuit of wisdom, every day something is dropped.”

The stakes are clearly lower for us than they were for Dodge’s smokejumpers. Still, it’s worth asking ourselves: which tools in our philosophical inquiry kit should we be prepared to drop, and under what circumstances? And how might we practise dropping them, so we don’t find ourselves unduly encumbered in the heat of the moment?

1 Sean Brady is the managing director of Brady Heywood (a Brisbane-based forensic forensic and investigative structural engineering firm) and host of the podcasts ‘Brady Heywood podcast’, ‘Saving Apollo 13’, ‘Simplifying Complexity’, and ‘Rethinking Safety’.

2 The Brady Heywood podcast episode ‘Why Expertise Can Hold Us Back’ is the recording of a conference presentation based on Sean Brady’s articles ‘Wedded to our Tools’ (parts 1 and 2, published in The Structural Engineer). The extended quotes in this post are excerpted from these two articles.

The Philosophy Club, based in Melbourne, works with students and teachers to develop a culture of critical and creative thinking through collaborative inquiry and dialogue.