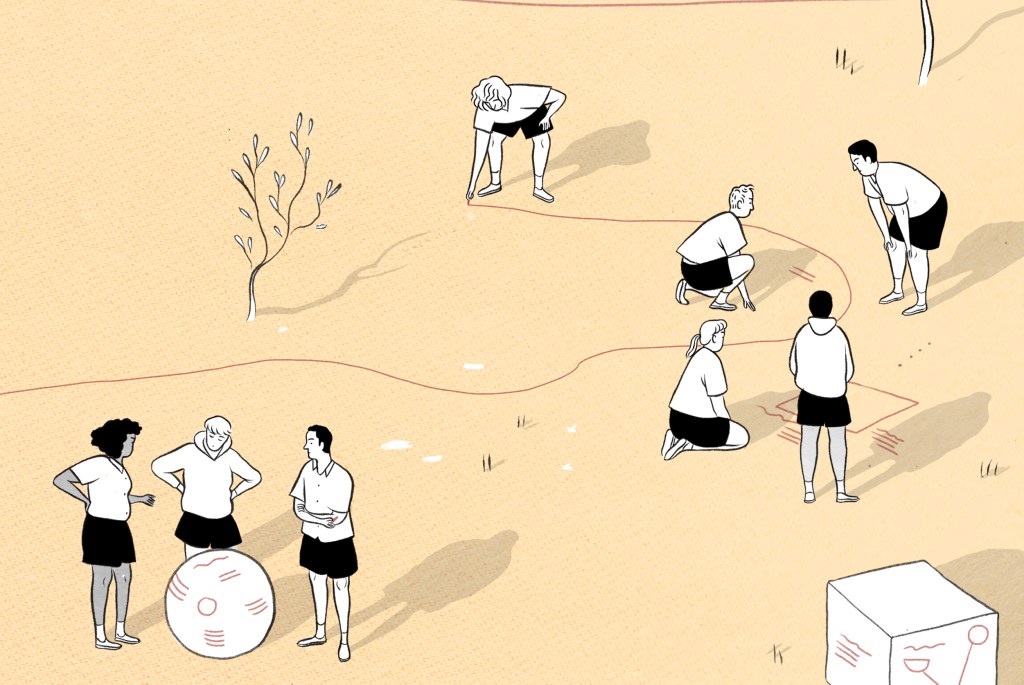

This State of the Nation essay was commissioned by Meanjin and originally appeared in Meanjin 83(2), June 2024. Thanks to Lee Lai for permission to feature a detail from her artwork above.

Some years ago, I met with the principal of an elite private school to pitch the benefits of The Philosophy Club’s programs. When I inquired whether the school would be interested, he gestured towards a state-of-the-art learning centre, recently constructed at a cost of over 30 million dollars, and mused: “Well, we’ve just spent all this money on a new building, so I guess now we’d better figure out what we’re going to use it for.” I was speechless. Here was a classic case of image mattering more than substance. When institutions are motivated by perverse incentives like acquisitiveness and status-seeking, their actions become toxic to our collective interests. But an antidote is within reach: the practice of collaborative reasoning.

Central to good reasoning is the dialectical process, in which conflicting arguments are pitted against each other and then integrated in a way that acknowledges their respective strengths and limitations. Thinking together with others helps us move through this dialectical process, something we often find difficult to achieve on our own. As philosopher Jack Russell Weinstein puts it, “thinking for oneself is a group activity.” When we undertake reasoning as a collaborative endeavour, it can help us frame problems constructively, clarify our commitments, spot flawed arguments, overcome dogmatic beliefs, and align our decisions with our values.

According to philosopher and sociologist Jürgen Habermas, the very institution of democracy depends on a thriving public sphere. This is an inclusive, non-coercive space for rational deliberation in which ideas are accepted through force of argument, and in which citizens can test the legitimacy of decisions made by their institutions. To participate effectively in the public sphere, we need to cultivate certain attitudes that are easy to describe but difficult to embody. We need to be critically receptive to alternative possibilities, inclined to consider them fairly, and intent on following arguments where they lead. We need to be open to criticism and willing to continually reassess the balance of evidence. We need to be sceptical and discerning, prepared to examine and test arguments, and vigilant about biases that might distort our thinking.

The touchstone of a flourishing public sphere is a widespread practice of collaborative reasoning. As philosopher Michael P. Lynch argues, “Democracies aren’t simply organizing a struggle for power between competing interests; democratic politics isn’t war by other means. Democracies are, or should be, spaces of reasons.” In the absence of a culture of collaborative reasoning, our public sphere has been debased in all manner of familiar ways. Too often, public officials are hustled, influenced or outright captured by mighty industries. Policy articulation is reduced to spin, slogans, and soundbites. Parliamentary discourse is combative and volatile. Journalists outcompete each other with ‘gotcha’ questions and an obsession with minor gaffes. Online conversations are degraded by polarisation, tribalism and misinformation. In social media ‘pile-ons’, individuals are silenced and ostracised for perceived transgressions. These threats to the public sphere are insidious: hairline cracks that point to the fragility of our democracy, like stress fractures in concrete signalling an underlying cancer.

We need new and stronger foundations.

For over a decade, I’ve been fostering deliberative education among young people through a practice of collaborative reasoning in schools. It’s a practice that education researcher Keith Topping refers to as “countercultural… actually quite revolutionary in the context of education as we know it”. Social scientist Brian Martin similarly observes: “Deliberation rather than debate—that is radical indeed.” I’ve created, in microcosm, inclusive civic forums that refine students’ thinking while fostering equitable participation. Student feedback reflects what for many has been a transformative experience: “[it] changed my perspective and made me think deeper”; “It was enlightening and thought provoking—I learned that even if you don’t have the same opinion, you can still talk about it without getting into an [adversarial] argument”; “I like the power it gives us [to] talk about meaningful things as a group…connected to our world and everyday life.”

Receptivity to new information often leads to a change of view. In one of my workshops, a true story about a series of uncanny coincidences provoked animated discussion about the existence of luck, destiny and miracles. Afterwards, I shared some details that rendered the story less extraordinary than it had first appeared. Could the coincidences be explained without recourse to luck? “I found that the first part of the story was pretty unbelievable,” said one student. “I thought it was impossible that this could happen. But when I heard the second part, it started sounding like this can happen… it’s pretty unlikely … but still possible.” Had anyone changed their minds about the existence of luck? “I’ve sort of changed my mind,” another student acknowledged. “I’ve kind of narrowed the circumstances where I use luck as an explanation. But I still think there is actual luck in some cases. It depends what you define as luck.” A third student demurred: “‘Luck’ is just a placeholder for ‘we don’t know the real cause’.”

My workshops extend an invitation for students to value and pursue collaborative reasoning with their peers. Rather than avoiding controversial issues as a matter of politeness, or skirting gingerly around differences of opinion, students practise communicating across cultural and ideological divides with care, empathy and intellectual humility. Like everyone else, they need space for intentional dialogue through which to negotiate and attempt to reconcile their differences. They need to forge relationships based on trust, authenticity, agency and self-determination, all necessary foundations for strong communities that are resilient to fracturing along the fault-lines of ideological difference.

As populism around the world accelerates, writer Michael Ondaatje observes that “political debate… seems no longer to be a contest between who’s right and who’s wrong, but … between who’s good and who’s evil. And if your opponent is evil, you don’t have to compromise, you don’t have to reach across the aisle; you have to destroy him or her.” Closer to home, in a victory speech on election night in May 2022, prime minister-elect Anthony Albanese chose a different narrative. He spoke of seeking “common purpose” and promoting “unity and optimism, rather than fear and division”. Securing a unified purpose depends on first establishing shared understanding, a lynchpin of healthy dialogue.

How do we open a space for shared understanding? I recall a class of children tasked with inventing their own communication system, equipped only with clay tablets and styluses. Faced with the challenge of denoting a fish, one child observed: “We don’t have to make it look like a fish, we just have to all agree that what we draw means fish.” Shared understanding begins with agreeing on certain conventions, including what we mean by particular words and norms of discourse.

Next, we need a new set of values. We have to care, collectively, about things like accuracy, coherence, significance and relevance. Once, my students were deliberating about gene-technology-assisted ‘de-extinction’. Some were strongly in favour, mounting arguments about its potential to address the biodiversity crisis, regenerate forests, and control climate change. Others objected, arguing: “This is just an inflated version of the problem of introducing species like the cane toad”; “Long extinct species might not be able to adapt to today’s environmental conditions”; “De-extinction might make us stop paying attention to endangered species because we’ll think: ‘We can always de-extinct them later’”; and “What’s to stop the species going extinct all over again?” Eventually, a student cautioned: “We shouldn’t just be looking at things from our [anthropocentric] perspective”. Another suggested: “We need to look at it from the widest possible perspective.” “Not necessarily the widest perspective”, responded the first student, “but the perspective that’s most relevant to the problem.” This is what I mean by valuing relevance, among other values of inquiry.

We need to prize not only speaking freely, but also attending to a wide range of voices, acknowledging common ground, and interpreting other views as charitably as we can. We need to de-escalate disagreement, express criticism respectfully, and be ready to make concessions or even change our positions. These are the dynamics that can restore our trust in each other as well-intentioned and reasonable counterparts, rather than as malevolent ‘others’ who are out of touch with reality, or unworthy of engagement. Until we shift our values, collaborative reasoning will remain an endangered species of public discourse.

The quest for shared understanding is particularly urgent in this post-truth age when corporate agendas, persuasive technologies and an unmet need for meaning have unmoored entire populations from consensus reality, nudging them instead towards radical ideologies rooted in conspiracy thinking, fundamentalism or nihilism. These ideologies spread faster the more efficiently social media platforms commodify users’ attention and entice them down internet rabbit holes. I’ve witnessed the effects of the alt-right pipeline in classrooms, with a recent and troubling rise in teenagers voicing racist and transphobic views influenced by the likes of Andrew Tate (widely regarded as ‘the king of toxic masculinity’). While schools grapple with misogyny and homophobia, some educators worry that talking directly about influencers such as Tate will promote them, but I share the view that in avoiding reasoned discussion “we are leaving young people vulnerable to these vile, insidious ideas, unable to recognise them as being extreme”.

Online radicalisation is one clear symptom of malaise. Another is the triumph of public relations over substantive exchange. In 2013, political journalist Michelle Grattan remarked that “Australia’s democratic system is like a healthy individual with a bout of the flu. It’s not seriously ill, but somewhat off colour.” Since then, the situation has only worsened. For each of the past five years, the global civil society alliance CIVICUS has rated Australia’s civic space as ‘narrowed’ (downgraded from ‘open’ in previous years). Perhaps too few of us noticed this as we rode the waves of Covid, extreme weather events, unstable employment and insecure housing, with our attention further diverted by Netflix, Instagram and a quicksilver pop cultural zeitgeist. Perhaps we weren’t paying enough attention as the government, hand in glove with tech corporations, permitted the rise of a surveillance economy that is now squeezing our democratic freedoms, discouraging dissent and criminalising protest. A climate of intimidation, oppressive as equatorial humidity, has burgeoned. Nonviolent activists intent on defending environmental and social justice have been imprisoned under draconian laws. Adversarial speech, sloganeering and shallow inquiry have revealed their inadequacy. It’s evident that we need more nuanced forms of political engagement to overcome the deadlock of our current system.

Interest is growing in citizens’ assemblies among other models of deliberative democracy. These models invite grassroots participation, restore trust in political institutions and release government from the disproportionate influence of privileged elites. In citizens’ assemblies, individuals collaborate to make careful evaluative judgements, taking into account swathes of complex information and varying degrees of uncertainty. These forums restore civility and argumentative complexity to often rhetoric-laden discussions of wicked problems.

If we were more accustomed to using collaborative reasoning to explore our tensions and to self-correct, we’d be less susceptible to demagoguery, less in thrall to powerful institutions, and more inclined to trust one another.

We need to practise. Democratic renewal is waiting in the wings.

……………………………………….

The Philosophy Club, based in Melbourne, works with students and teachers to develop a culture of critical and creative thinking through collaborative inquiry and dialogue.

Leave a comment