8:30pm, Wednesday: My seven year old was tucked up in bed, reading aloud from Patricia MacLachlan’s Wondrous Rex, when she came to a passage about a character named ‘Daniel’.

She pronounced the name with emphasis on the last syllable. I corrected her, pointing out that ‘Danielle’ is a girl’s name and ‘Daniel’ is a boys name. All of a sudden she was beside herself, sobbing uncontrollably: “There’s no such thing as girls’ names and boys’ names!”

I was taken aback by the intensity of the outburst and found myself stifling giggles. That’s until I realised that her passion was rooted in empathy. “I don’t want nonbinary kids to feel excluded”, she wailed, distraught. “You’ve got to say ‘traditionally’. Danielle is traditionally a girl’s name, but anybody can be called anything they like.” I was listening intently. She saw she was getting through to me, and her distress ebbed.

“It’s good that we can talk about this stuff, isn’t it?” I asked as we shared a cuddle.

Her reply was poignant: “I wish that just by having a conversation with you, the world would change.”

Adults often comment on children’s strong sense of justice. But kids, no matter how true their moral compass, are typically assumed to be — or feel themselves to be — puny agents in a vast and inscrutable world; a world in which power is wielded often invisibly by adults and the institutions they’ve created.

While kids share in the fruits of historical efforts to improve the world, they also inherit a legacy of past wrongs. For one thing — and it’s a biggie — they’re reluctant heirs to the great unravelling: grave harms and epic losses that spring from the negligence, ineptitude and self-interest of previous generations. And children play their own part, whether by challenging, upholding or submitting to the norms by which we live. They can’t help but participate, somehow, in the issues that overshadow our days: climate collapse, mass extinction, pandemics, refugee crises, threats to civil society, and social injustices like gender inequality, trans inequality and nonbinary exclusion.

………………………………………………………

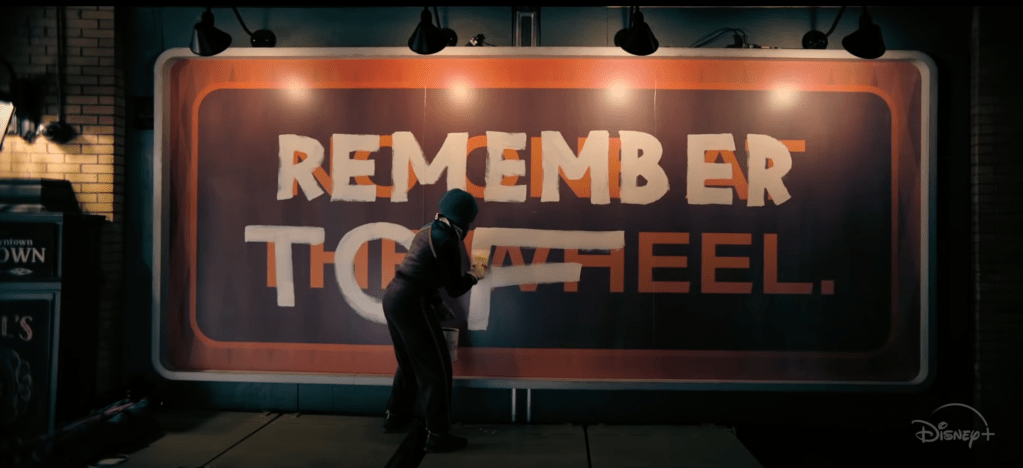

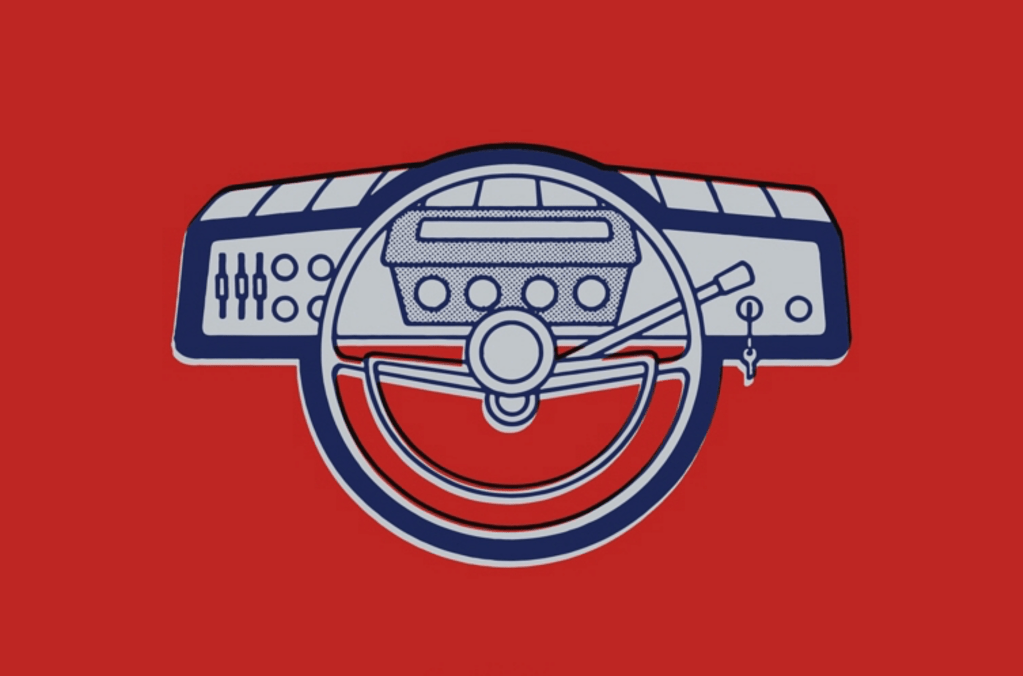

Family TV nights in my household have lately been devoted to the glorious kids’ adventure series The Mysterious Benedict Society, based on the books by Trenton Lee Stewart. The plot of Season 1 revolves around ‘The Emergency’, a pervasive but enigmatic state of affairs that dominates the news and neighbourhood chatter in the fictional metropolis of Stonetown. “Was it always like this? Bad news all the time?” a plaintive child asks in the opening episode. Later in the series, another child quotes a succession of news headlines: “‘Emergency!’ ‘Doom!’ ‘No one at the wheel!’”

‘There’s nobody at the wheel’ turns out to be a recurrent motif, appearing on billboards and on townspeople’s lips. Meanwhile, workmen are seen papering over an old billboard urging ‘Things must change NOW!’, replacing the faded posters with fresh ones bearing the identical demand, which has clearly gone unheeded.

One critic observes that The Mysterious Benedict Society seems to be set in a universe just to the left of our own. Parallels with real life are easily discernible through the sheer fabric of metaphor. “I suspect parents will feel more than a little empathy of their own for these characters trapped in a world where every day brings new worries we, as individuals and caretakers, can do little to solve,” another critic writes. But The Mysterious Benedict Society is a work of fiction, in which it’s perfectly possible for a crack team of kid detectives to uncover the source of The Emergency and, well, save the world. Is such youthful heroism remotely plausible in reality?

Here’s what we know. Recent studies in The Lancet have found that ‘The future is frightening’ for 75% of children and young people and that climate change-related anxiety and PTSD are a planetary health issue for young people in Australia. Young people are riddled with existential worry and many feel compelled to act.

Together with my collaborator Grace Lockrobin (P4C Director of SAPERE, and Founder and Executive Director of Thinking Space), I’ve recently been documenting the hope, fear, shock, cynicism, bleakness and courage voiced by children as they confront the realities of the climate and ecological crisis. When Grace posed the question ‘Are you too small to make a difference?’, children aged 8 – 11 variously responded:

Luca: “Even though we can make a difference, I keep feeling that it isn’t enough. There’s more people that ignore [the crisis] than people that don’t, which makes… our efforts more in vain.”

Kai: “We are the ones who’ve been given the choice to make the change… A lot of people are going out onto the streets, and I feel that we – not just me, but all of us can together make a change.”

Xanthe: “I think that young people have to fix it, because we may not have got us into the situation, but if we start fixing it now, we will learn habits – good habits – and those habits will make a big difference.”

Luca: “[We should act], not because [young people] caused it, but because… age doesn’t matter in this. What matters is the quantity of it [climate action].”

Kai: “I think we should also be part of this because… in the end it’s our future. It’s our future that’s going to be changed.”

The children then considered a news headline quoting Greta Thunberg’s comment that ‘school strikes have achieved nothing’, citing a 4% rise in greenhouse gas emissions in the period 2015–2019.

Asked to contemplate the effectiveness of the youth climate protests, some of the children were despondent:

Skye: “It actually hasn’t made a difference in the bigger picture … because governments still aren’t doing anything about it, and there’s still climate change. So no matter how many people… start rebelling against it, it’s whether or not the people who are in power, like the government, choose to actually listen or not.”

Luca: “The government are way above our reach… The government won’t listen to us; we are just little kids, and the government doesn’t listen to little kids.”

Others were more sanguine:

Kai: “One person has encouraged many, many other children to join this school strike rebellion, and it just shows … that even though you’re small compared to the ginormity of the world, you’ve still made that difference, and it’s actually turning eyes onto the fact that we have an actual serious climate crisis here.”

Rebecca: “If everybody did that – if everybody went and told one person ‘oh you should do something about the environment’, then maybe that will make some sort of major difference on the climate crisis. And I genuinely think that is why no one is too small to make a difference.”

Some were ambivalent, feeling personally impotent and yet convinced that action is crucial.

Sasha: “I feel like I’m too small to do anything, but also really think it’s really important, super important [that] people should do… [the] biggest things possible.”

James: ”For me, it’s: ‘I’m too small to do anything’. And then I also think the crisis is important. And what we do now, matters.”

In the role of facilitator, Grace observed: “It sounds like a little bit of a paradox there. You think that what you do matters, but also that you’re too small to make a difference. Can you help us untangle that?”

James responded: “I think what people do – [what] lots of people, like crowds – do, matters… Collective action can work. It’s got to be lots, instead of one, for something to actually happen.”

The climate and ecological crisis is indeed The Emergency of our times, and awareness is growing. From the seeds of Greta Thunberg’s School Strike for Climate, a worldwide movement of youth activists has emerged. Emboldened and vociferous, young people are demanding urgent crisis mitigation through initiatives like Fridays For Future and Powershift, and organisations like the Australian Youth Climate Coalition and Climate Justice Alliance. While youth activists acknowledge Greta Thunberg as the movement’s inspiration and catalyst, it’s been a team effort: “Together we have started a revolution,” one remarks, while Greta herself says: “I would never have imagined that it was going to be this big… I think this is just the beginning of the beginning of the movement. I think we haven’t seen anything yet.”

It was a child who — as the folktale goes — declared ‘The Emperor has no clothes’, and it’s children again who are daring to speak the truth: extractivist industries and their billionaire backers are at the wheel, and things must change NOW.

………………………………………………………

This post commemorates World Philosophy Day 2022 in hopes that practices of philosophical enquiry will increasingly be applied to pressing ethical, social and political issues in contemporary life.

I’ve shared some more of the children’s responses to the climate and ecological emergency in my previous posts We Don’t Want the World to Die and A Thriving Public Sphere. To discover more about the themes addressed here, please view Grace’s talk Philosophy and the Fight for the Future; her public philosophy workshop Ethics and the Environment concerning hope, despair, human nature and climate action; and Too Small to Make a Difference?, the recorded discussion about climate activism that Grace expertly facilitated among children as part of our joint project.

………………………………………………………

Postscript

As the international climate conference COP27 draws to a close, I’ve been wondering to what extent young people’s voices have been heard there. I’ve found relatively little media coverage about youth participation in the conference, but in the lead-up Ceri Putnam reported the following at CarbonTracker.org:

“[In] a notable change to the annual event, COP27 is pioneering a designated official space for youth and children at the UN event… COP27 will highlight the need for youth involvement in climate discussions, with a themed ‘Youth and Future Generations Day’ included in the schedule.

Historically, sustainable development has been defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” However, rarely have those future generations been invited into the conversation of policy makers…

The ultimate test will be whether those voices are heard or if the inclusion is a tokenistic ‘youthwashing’ PR move. Whilst a few key youth activists have stood out in recent years, such as the prominent Greta Thunberg, Licypriya Kangujam and Haven Coleman, to name a few, politicians and corporates have also been seen to adopt the intergenerational framing to further their own agendas. This has led to youth members’ frustration in being used as a marketing tool rather than given a meaningful ‘seat at the table’. It is hoped that COP27 will deliver a true platform for engagement and debate between all attendees.”

………………………………………………………

The Philosophy Club works with students and teachers to develop a culture of critical and creative thinking through collaborative inquiry and dialogue.

Leave a comment