Ever on the lookout for innovative teaching resources, I jumped at the invitation to preview a sample of The Blob Guide to Children’s Human Rights, a new release in the popular Blobs series (Taylor & Francis: Routledge). Regrettably, on my assessment, the book compromises rather than adds value to the literature on human rights education. Here I offer my critique, followed by my recommendations of other books and resources that I believe would better support the teaching of human rights (and specifically children’s rights).

‘Blobs… are a variety of characters expressing a variety of feelings…

Blobs live in a strange world that our eyes cannot see but our heart can discern’

– Wilson & Long

The authors note that the ‘Blobs’ were originally designed with a focus on feelings and body language, and were intended to help people to ‘”read” the world emotionally’. As initially conceived, then, the ‘Blobs’ were a tool to support socio-emotional development. This new book represents a shift in focus, whereby the ‘Blobs’ are being introduced as a tool to support human rights education. Bringing together these two domains poses certain challenges, as human rights education and socio-emotional learning use different conceptual frameworks. Rights-based discourse is concerned with concepts like respect, dignity, autonomy, individuality, entitlement, duty, protection, and violation, whereas socio-emotional discourse is concerned with concepts like sympathy, kindness, cruelty, hurt, solidarity, need and helplessness.

To what extent these two domains can be reconciled is a question for philosophical reflection. A book of this nature, combining an emotions-focused tool with rights-focused content, needs to be thoughtful in its treatment of the relationship between the domains. Yet the authors gloss over it with the brief statement: ‘Feelings are so important to encourage if we are to recognise the way that abuses of Human Rights make us all suffer.’

The book’s failure to deal with the tension between the socio-emotional and human rights frameworks leads to what I see as a significant problem. In the socio-emotional domain, the emphasis on subjective experience leaves room for the kind of relativism that the authors articulate: ‘the Blobs can be interpreted in a hundred different ways. There is no right and wrong about the Blobs’. By contrast, in the human rights domain, the emphasis on the universality and objectivity of rights necessitates rational justification, shared evaluative standards, and public accountability. For rights to have weight, their meaning must be broadly agreed upon. It is erroneous, not to mention dangerous, to imply that ‘there’s no right and wrong’ about human rights. The book therefore suffers from a misalignment between the prescriptiveness and universality of rights, and the contingency and variability of emotional responses.

Equally concerning is the book’s lack of depth. Complex issues are treated in a superficial way, and readers are not encouraged to engage in rigorous thinking. The authors seem unconcerned with fostering analysis, justification, or critical evaluation, opting instead for having students share their feelings and opinions. The authors endorse the relativist claim that ‘There are no right or wrong answers.’ By contrast, a philosophical approach to human rights education would make it clear that although there may be no single right answer to questions like ‘What does it mean for a child to be safe?’ or ‘Why is privacy important?’, there are various ways of being wrong, for instance by responding with unfounded or nonsensical assertions, or with inconsistent or fallacious arguments. Had the authors taken a more philosophical approach, they might have promoted a deeper exploration of contested concepts, a more critical understanding of the meaning of the rights being explored, and a more considered appreciation of the value of those rights. The scope could also have been enhanced by encouraging attention to the place of rights in the context of students’ personal, social, emotional and political lives – including assessing the extent to which various rights are upheld, and deciding how best to respond to rights breaches.

Given the centrality of the book’s illustrations, there is a troubling lack of clarity concerning their interpretability. The authors have suggested that there’s no wrong way of interpreting the blob illustrations. They state: ‘the Blobs can be interpreted in a hundred different ways. There is no right and wrong about the Blobs… A leader who uses them in a ‘one way of reading them only way’ [sic] will find that the rest of their group become very frustrated in discussions. Each picture is a means to a conversation, rather than a problem to be solved or a message to be agreed upon. If the people you are working with read the characters in totally opposing ways, that’s fine.’

If we take this at face value and accept that there is no wrong way to interpret a ‘Blob’ illustration, then –– in the case of the ‘Blob’ illustrations of rights in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) –– it follows that there is no wrong way to interpret the rights themselves. Yet the rights in the UNCRC have specific meanings, and there are indeed wrong ways of interpreting them. Hypothetically, if I were to read Article 16 (‘Children have the right to privacy’) and I interpret it to mean that children should keep sexual abuse secret, then I have wrongly interpreted the Article. When it comes to interpreting rights, it is dangerous to imply that ‘there’s no right and wrong’.

Perhaps the authors intend for only some of the ‘Blob’ illustrations to be open to interpretation. There are certainly places in the sample text where the authors reveal the intended meaning of a particular illustration, although that meaning is not always intelligible from the illustration itself. For example, the authors express Article 11 of the UNCRC as: “Every child has the right to live in the country they are supposed to stay in.” The accompanying illustration is rather ambiguous:

The small figure is clearly a child, and the figure on the right is labeled ‘MP’, but it’s not clear who the angry figure on the left is – a protector, or a menace to the child? I interpreted the illustration to depict a parent protecting a refugee child from a government deportation order that contravenes the UNHCR Refugee Convention. However, when I researched Article 11 of the UNCRC, I found the clearer articulation: “Governments should take steps to stop children being taken out of their own country illegally”, suggesting that this illustration in fact depicts a government minister halting the illegal removal of a child –– a very different scenario. The inherent ambiguity makes this illustration a hindrance, rather than an aid, to understanding what is meant by the right enshrined in Article 11.

The book introduces a range of themed illustration sequences intended as five-point scales on which students can indicate their responses to suggested questions. These convey some questionable notions. For instance, the illustrations in the ‘Listening’ scale suggests a false dichotomy between speaking and listening and implies that speakers cannot also be good listeners.

‘the careful listener’, as though these were polar opposites

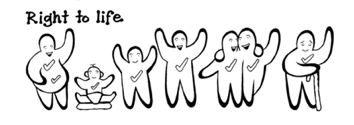

The ‘Right to life’ sequence (below) conveys a disturbing notion that the right to life diminishes over the life-course, and that a couple has less of a right to life than a single person. It is hard to see what is achieved here, as any ranking of different people’s ‘right to life’ seems to runs counter to the spirit of human rights as ‘rights for all’.

In my view, then, The Blob Guide to Children’s Human Rights falls short on a number of levels. Readers interested in human rights education may instead wish to seek out the following high-quality books that combine words and pictures to offer a bird’s eye view of all (or many) of the rights enshrined in the UNCRC:

I Have the Right to Be a Child by Alain Serres, Aurelia Fronty and Sarah Ardizzone (trans. Helen Mixter)

This Child, Every Child: A Book About the World’s Children by David J. Smith and Shelagh Armstrong

For Every Child by Carline Castle and John Burningham (Foreword by Desmond Tutu)

A Life Like Mine: How Children Live Around the World by Dorling Kindersley

Every Child A Song by Nicola Davies and Marc Martin

Our Rights: How Kids are Changing the World by Janet Wilson

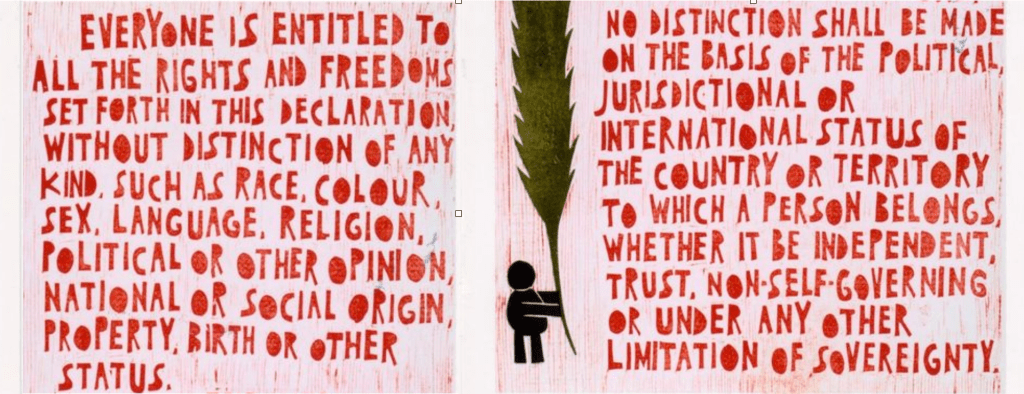

In a similar vein, numerous books visually represent the rights enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights. These include:

We are All Born Free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures published in association with Amnesty International

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights illustrated by Michel Streich

Universal Declaration of Human Rights by Meredith Stern

In addition, there are many excellent picture books for children on a broad variety of themes pertaining to specific human rights, for instance:

Dreams of Freedom by Amnesty International

Malala: Activist for Girls’ Education by Raphaele Frier and Aurelia Fronty

The Day You Begin by Jacqueline Woodson and Rafael Lopez

Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation by Duncan Tonatiuh

There is also a diversity of books and online resources that are not primarily visual, but provide discussion prompts and classroom activities that promote knowledge and understanding of children’s rights. Among these are:

ABC Teaching Human Rights: Practical Activities for Primary and Secondary Schools (United Nations)

Stand Up for Children’s Rights: A Teacher’s Guide for Exploration and Action with 11 – 16 year olds (UNICEF)

Bringing Child’s Rights Into Your Classroom (SNAICC)

………………………………….

The Philosophy Club works with teachers and students to develop a culture of critical and creative thinking through collaborative enquiry and dialogue.

Leave a comment