Ed Bailey’s legacy and the power of community youth theatre

For over fifty years, in the scout halls and basements of Melbourne’s inner east, children who rarely speak up in class have discovered they can command an audience. Teenagers have pushed back against social pressures to conform, celebrating each other’s quirky brilliance—and even their glorious failures. At the heart of it all was Ed Bailey, a retired university IT lecturer who seemed to understand that education doesn’t only happen in classrooms.

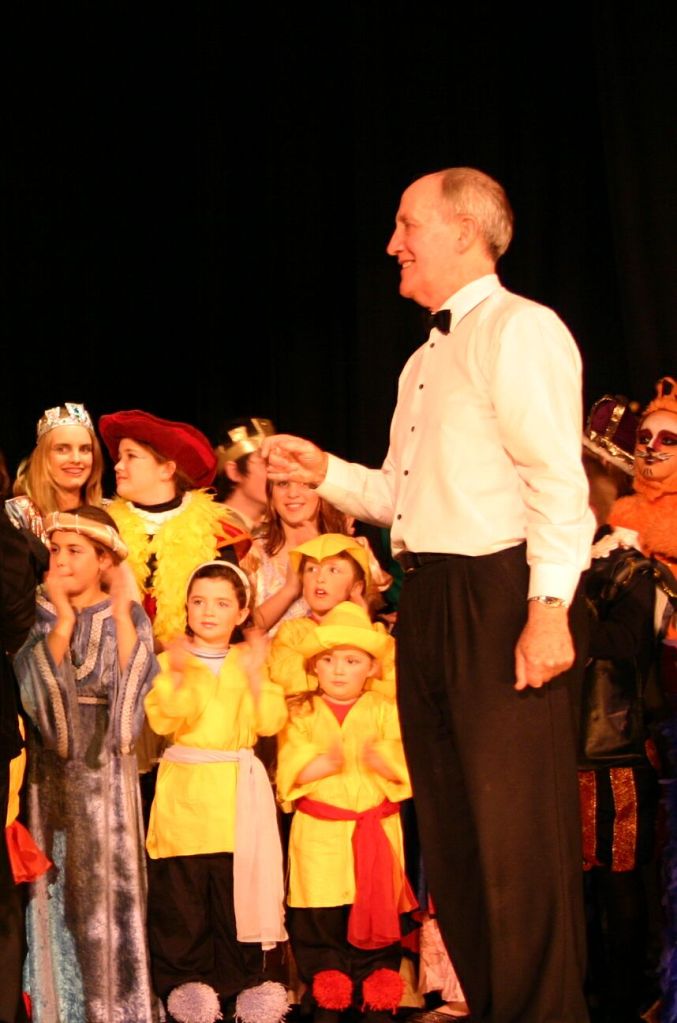

Ed Bailey and his wife Maureen founded Track Youth Theatre in 1980 as an offshoot of the Toorak Players, staging its first musical theatre production with a cast of 25. By the following year, the group had doubled in scale and found a stable home at a local theatre. For the next 33 years Bailey wrote scripts, music and lyrics, directed the young talent, and nurtured what would become one of Melbourne’s most enduring community theatre groups. Track staged 50 productions before Bailey stepped down almost a decade ago, passing the torch to a new generation of leaders—including its current director, Sophie Jevons.

This month we remember Bailey, whose recent death has left a void for the families—mine included—whose children grew and thrived because of what he created: an inclusive space for self-expression and collective effort. Because of what he created, Track is a diverse community of young people who hone their skills in drama and stagecraft before staging an annual musical theatre production.

What Bailey understood on an intuitive level aligns with what educational researchers have long argued: Learning is most powerful when it’s collaborative, embodied, and purposeful. Youth theatre exemplifies what Paulo Freire called a “pedagogy of possibility”, where young people exercise hope, creativity, and a capacity to enact change. Community theatre the world over affords this kind of transformative potential. One UK mother, watching her selectively mute child recite every line faultlessly, described it as “a monumental turning point”.

Bailey gave kids reasons to cooperate. In mixed-age groups, they tackle complex creative challenges and take collective responsibility for a shared artistic vision. They research characters, solve technical problems, negotiate creative differences, and ultimately present their work to a live audience. In the process, they develop self-confidence, social awareness and emotional resilience. Track Youth Theatre exemplifies what educational philosopher John Dewey called “learning by doing”. Rather than learning in the abstract about collaboration and empathy, the participants live these values, working together to embody different characters and perspectives.

Actor Stephen Curry, who started at Track at age 11, recalls that “Ed taught me about concentration, communication, co-operation and commitment.” While sparking a love of performance, Bailey ensured that his young charges projected their voices, didn’t upstage other actors, and never peeked through the curtains. These seemingly simple lessons—communicate clearly, respect your peers, exercise self-restraint—are profound life skills.

Bailey’s approach was radically inclusive: no auditions, everyone gets a line, and every role matters, regardless of skill level. That spirit continues today, infusing the group’s ensemble work. But the story of Track also points to a troubling aspect of the youth theatre scene. Whereas young orchestral musicians benefit from public funding, aspiring musical theatre performers face systemic neglect and often “have to pass family income and parental energy tests right at the start” (Barnbrook, 2016). With private drama schools costing thousands, community groups like Track are more vital than ever, serving as democratic spaces where anyone with enthusiasm and commitment can participate.

At 77, watching the final production he directed, Bailey reflected: “The whole thing is a joy when you see what the kids get out of it. They get a big buzz out of it.” In a world increasingly focused on narrow definitions of success, Bailey’s legacy reminds us that the most important learning often happens in community spaces where young people are entrusted with real responsibilities.

With Ed Bailey’s death, another curtain has fallen—but for all the kids who learned at Track that their contributions matter, his influence lives on.

……………………………………….

Postscript, 21/07/2025

For anyone interested in the links between youth theatre and collaborative philosophical inquiry, I recommend Erica Preston-Rodder’s excellent article: What can philosophy learn from improvisational theater?

……………………………………….

For over a decade, The Philosophy Club, based in Melbourne, has worked with students and teachers to develop a culture of critical and creative thinking through collaborative inquiry and dialogue. Although we are no longer instigating projects, we remain open to proposals from schools and other organisations.

Leave a reply to Christa Crowe Cancel reply