On 4 December 2019, the Morrison government repealed Australia’s Medevac legislation. Medevac was life-saving legislation enabling refugees on Nauru and Papua New Guinea to get critical medical treatment. The Medevac legislation was originally passed to stop politicians from overriding offshore Australian doctors’ clinical decisions. Politicians were consistently interfering with doctor’s decisions, placing patients’ health and wellbeing at risk. A Queensland coroner found that one young man died because he wasn’t provided the treatment and transfer doctors asked for. As a result of this dire situation, Parliament passed Medevac to ensure Australian doctors could make their life-saving decisions without political interference. The repeal of Medevac had devastating consequences on the hundreds of refugees who had already arrived in Australia under the legislation, and who were subsequently detained indefinitely in violation of the UN Torture Convention which prohibits subjecting people to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

January 26, 2020

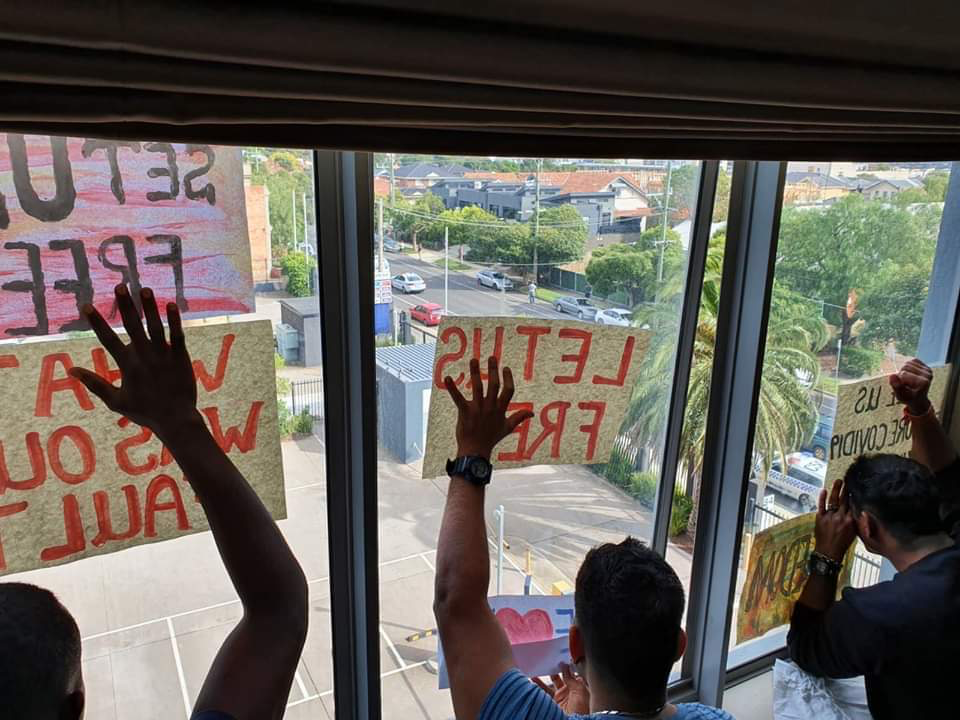

Yesterday evening I drove ten minutes from my suburban home and stood in a hotel carpark and sang to a group of young men I’ve never met. I couldn’t get close enough to speak to them, but we waved to each other through the hotel’s third-floor windows and I tried to express my complex emotions through song and gesture.

I stood among 40 singers and instrumentalists, and the young men in their respective hotel rooms pressed their raised arms to the closed window panes and shaped their hands into love-hearts which they directed towards us.

These sensitive souls are among the 180 refugees and asylum seekers who have been indefinitely held in hotels and apartments and detention centres around Australia, after being transferred under the Medevac urgent medical treatment program. (That is, before our Government callously repealed the Medevac legislation last month, leaving sick asylum seekers to languish indefinitely in horrifying conditions in offshore detention centres.)

You might imagine it’d be a relief for those ‘lucky’ Medevac evacuees to enter Australia after enduring years of detention on Manus Island or Nauru, where they suffered not only a loss of freedom but also repeated violent attacks and robberies, accompanied by scandalous inaction by police, with inadequate hospital care for their multiplying physical and mental health conditions.

Yet their welcome to Australia has been far from hospitable. For five months they’ve been held under guard, in some instances in hotel rooms like the ones we visited in Preston, unable to interact with other hotel patrons or the wider community. “It’s much worse than Manus because I suffer from asthma and I need an outdoor space,” said Moz, a Kurdish refugee interviewed by the Guardian. “I am like a hostage… They have locked me up in a hotel and there is not any outdoor space for breathing. It’s not an easy situation.”

Imprisoned and isolated for 19 hours a day, these young men can only go outside if they get permission to be transferred for short periods to a concrete area of the immigration detention centre in Broadmeadows. It can take days to be granted this permission, and then the additional security at the detention centre can trigger episodes of PTSD.

What’s more, in a terrible irony for a medical evacuation program, Moz and his fellow asylum seekers have received scant medical treatment for their chronic dental problems, post-traumatic stress and other illnesses.

The Human Rights Commission has condemned the detention arrangements, the lack of dedicated facilities, restrictions on freedom of movement and inadequate access to open space. Worse still, the men face an uncertain fate, with Australian Border Force suggesting they may well be sent back to PNG.

“It’s very ambiguous, they don’t tell us anything, they don’t give us any hope, they have created this game in order to break our hearts, they don’t want to do anything for us,” Moz told The Guardian.

It’s well known that prolonged detention is a risk factor for mental ill-health, with the negative impacts worsening as the length of detention increases. “What causes most harm is limited choice, perpetual uncertainty, and, of course, powerlessness,” refugee advocate Jane Salmon says, arguing for community detention and resettlement in place of the current inhumane arrangements.

Kon Karapanagiotidis of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre puts it plainly: “The government must not be allowed to recreate its model of secrecy and abuse of human rights that characterises offshore processing here in Australia, and must be held accountable for medical neglect that is causing unimaginable harm.”

Of course, we must hold the government to account.

And at the same time we must connect with those who are detained and let them know we remember them; that despite our government’s rampant xenophobia, there are still Australians who care about human rights and who will fight for those rights and freedoms on behalf of the people who have been denied them.

So last night we waved to the men and we blew kisses and shouted out messages of support. We sang and played music and danced. We recognised these men as individuals. We saw the emotion in their faces and we looked into their eyes and I thought: “There but for the grace of God go I.” At one point a large flock of currawongs flew overhead and we all gazed up, sharing a moment of appreciation for the freedom of their flight.

I cried for the men detained and for the culture that allows this dangerous and unjust imprisonment to happen on our watch, in our own suburbs. Then I wiped away my tears and hugged my new friends in the hotel carpark and I committed to take more action.

My (refugee) grandparents were migrants to Australia, as were the ancestors of everyone I know, with the exception of my Indigenous friends with whom I’ll be standing in solidarity today, as we mark Invasion Day.

So many of us, sharing a once-foreign land, trying our best to make a contribution and often taking our freedom for granted.

1 April, 2020

Thousands of refugees and asylum-seekers have been forgotten in Australia’s COVID-19 crisis plan. They’re excluded from Medicare and Centrelink safety nets. They’re highly vulnerable to unemployment. And they’re reliant on overstretched charity and community support for basic necessities like rent, food and health care. Many are facing extreme poverty. We cannot let this continue.

The inhumane and unjust imprisonment of refugees in detention centres must end now, as COVID-19 adds yet another layer of risk to their already compromised lives – lives already marred by continuing medical neglect and psychological abuse.

We will not be passive bystanders.

The government’s treatment of these innocent people is an intolerable breach of human rights and has made Australia a pariah among nations.

If we don’t act now, more lives will be gravely endangered. Immediate release is a moral obligation.

19 July, 2020

Seven years is way too long. Seven years of cruel and unjust detention of refugees. Seven years of refugees detained in horrendous conditions on Manus and Nauru, and now also in overcrowded detention facilities here in Australia. Hundreds of innocent people from backgrounds of torture and trauma escaping terrifying circumstances with the hope of a better life, only be locked up indefinitely (as though they were the worst kind of criminals).

I stand with the refugees and asylum seekers locked up by the Australian government. They are innocent and vulnerable survivors of danger, hardship, torture and trauma who deserve our sympathy and support — and yet they’ve been unjustly imprisoned for seven years without the freedom, dignity and the human rights that are owed to everyone. Their treatment has been callous, punitive and monstrously inhumane. And now their cramped detention quarters place them in grave danger of coronavirus infection. They must be freed.

I invite you to think back over the last seven years of your life. Me, I’ve been pregnant, helped to raise our daughter from babyhood through to the start of school, developed my business, travelled, made new friends, taken up new skills and projects. And I’ve enjoyed all the little freedoms of daily life, like taking walks in the sun, breathing fresh air, seeing my friends and family, and eating what I want.

Imagine erasing these experiences of freedom and replacing them with seven years of detention and oppression. Locked up in a small room 23 hours a day, subject to the petty tyranny of security guards who do arbitrary things like taking away your pencil and paper when they see that drawing is your key to sanity. Seven years of boredom, frustration, depression, futility. Seven years of declining mental and physical health.

Many of the refugees on Manus and Nauru were transferred to Australia under the Medevac legislation in order to get medical treatment for their health conditions. Tragically they have not received adequate healthcare, but they are still being held in detention — at a cost of more than $346,000 per refugee per year.

On top of this, those in detention are at much higher risk of contracting Covid-19, being unable to physically distance or properly open windows for sufficient air circulation. A staff member at the overcrowded Mantra detention facility recently tested positive for Covid-19. The potential for an outbreak among the refugees there is devastating.